Med Mind: IoT for Managing Dementia

Med Mind: An automatic pill dispenser and home cognitive monitor

In the summer of 2019, I was a part of Invent@IITGN, a rigorous 6-week program in inventing, prototyping and patenting at IIT Gandhinagar. Along with my incredible partner Arpita, I successfully prototyped a proof of concept and applied for a patent in India and USA. The device was targeted to elderly patients with cognitive impairments, or patients in the early stages of Dementia. It operates on IoT, and unlike a simple-off-the-shelf product, this device comprises a whole system of cognitive health monitoring, which hasn’t been done before!

My Role: Research, Ideation, Prototype, Patent Writing, Presentation

Timeline:

6 weeks

Deliverables: Working proof of concept, Patent application to India and USA

What is Med Mind?

Med Mind is a pill dispenser designed especially for elderly patients suffering from cognitive impairments. The device can be broadly categorised into 3 essential functions:

How it works

01 At the time of dose, a preset alarm and light act as reminder.

02 To disable the alarm, the patient pushes down on the top button. (like any alarm clock)

03 The pills are dispensed after the patient completes a simple cognitive test.

04 After the tray is pulled out, a caregiver is notified via a mobile app.

05 After a period of time, say a month, data on the patent's cognitive health is shared with the doctor.

Process behind Med Mind:

The program required each team to come up with an idea, and present an iteration every week to a panel of experts. This meant that instead of following the conventional design process, we had to work in reverse. We would ideate, iterate and confirm through research. Every week some of our ideas would be modified and new features would be added. By the end of six weeks, we had a finished product and a full fledged patent application!

So, why Med Mind? I got the idea from my own grandfather who faced problems with medical management and was losing his cognitive abilities. My parents’ experience in helping him with his routine drove me to learn more about the problems faced by caregivers of the elderly.

Research

Every week while iterating on our device we would read through journals, other patents and even medical publications. To gain some specific perspective we consulted the counsellors at the IITGn Cognitive Science Lab, who have experience treating Dementia patients. While most of it was jargon, here's what we learned:

01

5% of all adults over the age of 65 are at risk of significant cognitive impairment.

Most of these adults take care of their physical health through medication and check-ups, but they often neglect their cognitive health. There are many ways to manage the medication routine of such patients, but no structured method that keeps track of their cognitive health

02

Current methods to keep track of cognitive health are cumbersome.

These include neuro-cognitive tests and asking caregivers about behavioural changes. Patients suffering from these diseases often refuse to sit for lengthy tests and this process is a challenge for the doctor, the patient and even the caregiver.

Dissecting the Invention

This program encouraged an iterative and hands on approach, so the design process was far from linear. Every week, we would present a different version of our device to a panel of 15 experts who would grill us on every aspect of our thinking. To explain our solution a little better, I have divided it into 3 essential parts.

Part 1 : The Cognitive Test

“Monitoring cognitive health” is what sets our device apart from every other medicine dispenser. We wanted to incorporate a simple testing mechanism into the device in an unobtrusive way. To do this, we came up with a series of tasks that can be completed using only a set of buttons and LEDs. They are modified and simplified versions of tasks already in use at cognitive science labs. It was important that the tasks be:

Simple, so they don’t irritate the patient or get in the way of her medication, and yet

Effective in capturing information about their cognitive health

These tasks record different parameters of cognitive health, depending on the progress of the patient’s disease:

Response Time

This task is for patients in whom the disease has progressed significantly, but who continue to live without constant care. One out of the three lights randomly turns on after the alarm is disabled. The patient has to press the corresponding button, and the pills are dispensed. We calculate the time it takes the patient to “respond” to the light after each dose.

Short-term Memory

This task is for patients who are in the early stages of the disease and show only a few of the symptoms. Following the alarm button, the lights blink in a sequence and the patient has to copy the sequence correctly.

Colour

This task may be added to the device as an additional feature, and is for patients with colour vision. If the colour of the buttons is changed accordingly, the LEDs may light up in a certain colour and the patient has to push the button of that colour. Losing colour perception is an important marker of cognitive impairment.

On further research, many such tasks can be added to the same device. After each dose (and for all kinds of tasks), the device computes the following data:

Failure or success of the task

Time taken to perform the task

The pills are dispensed regardless of success or failure (since the primary goal of the device is to dispense medicine.) Periodically, for eg. every 30 days, this data is sent to a doctor. This can indicate the patient’s cognitive status to the doctor so he can assess whether further check-up is needed.

Part 2: Medication dispensing

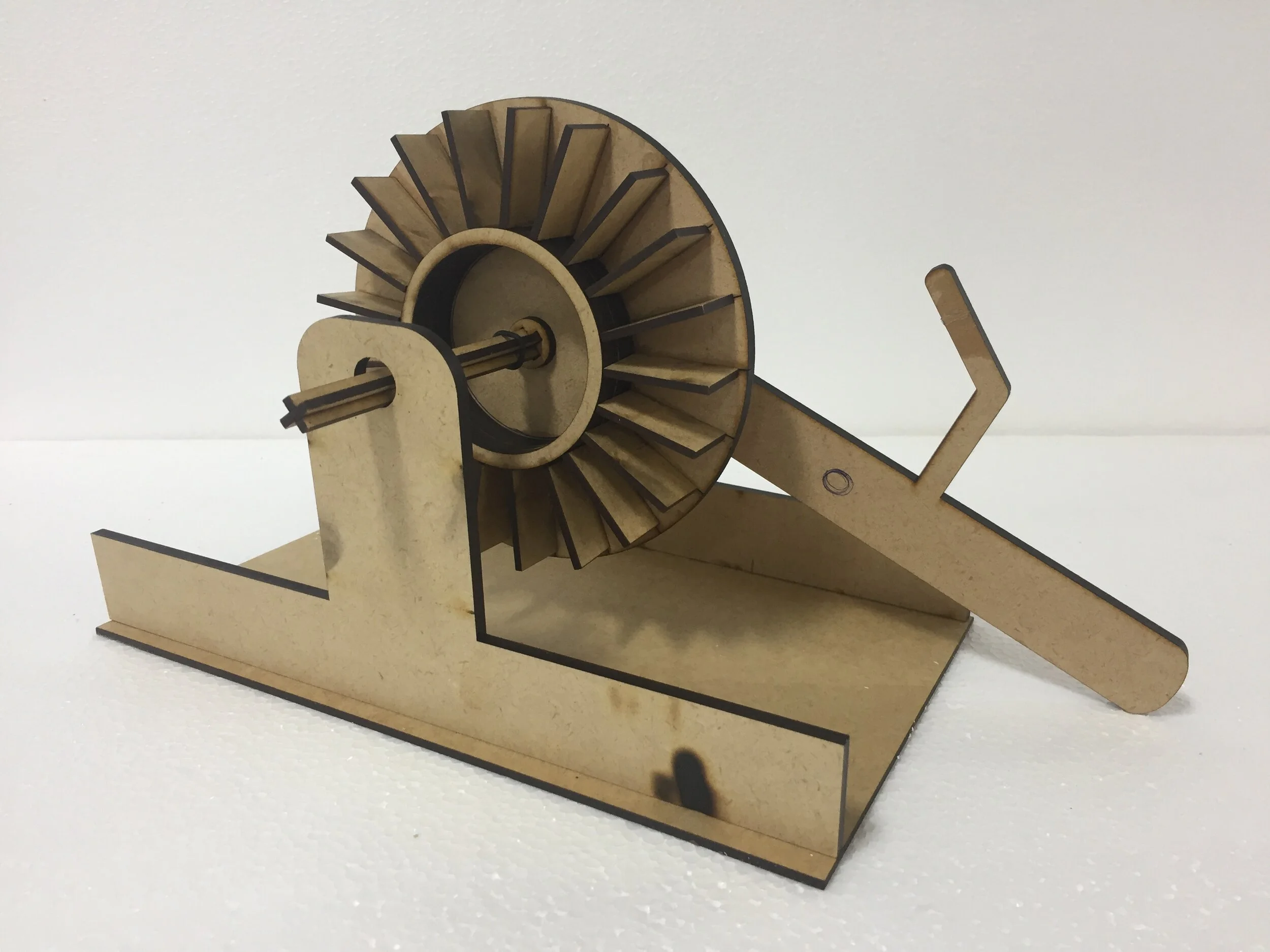

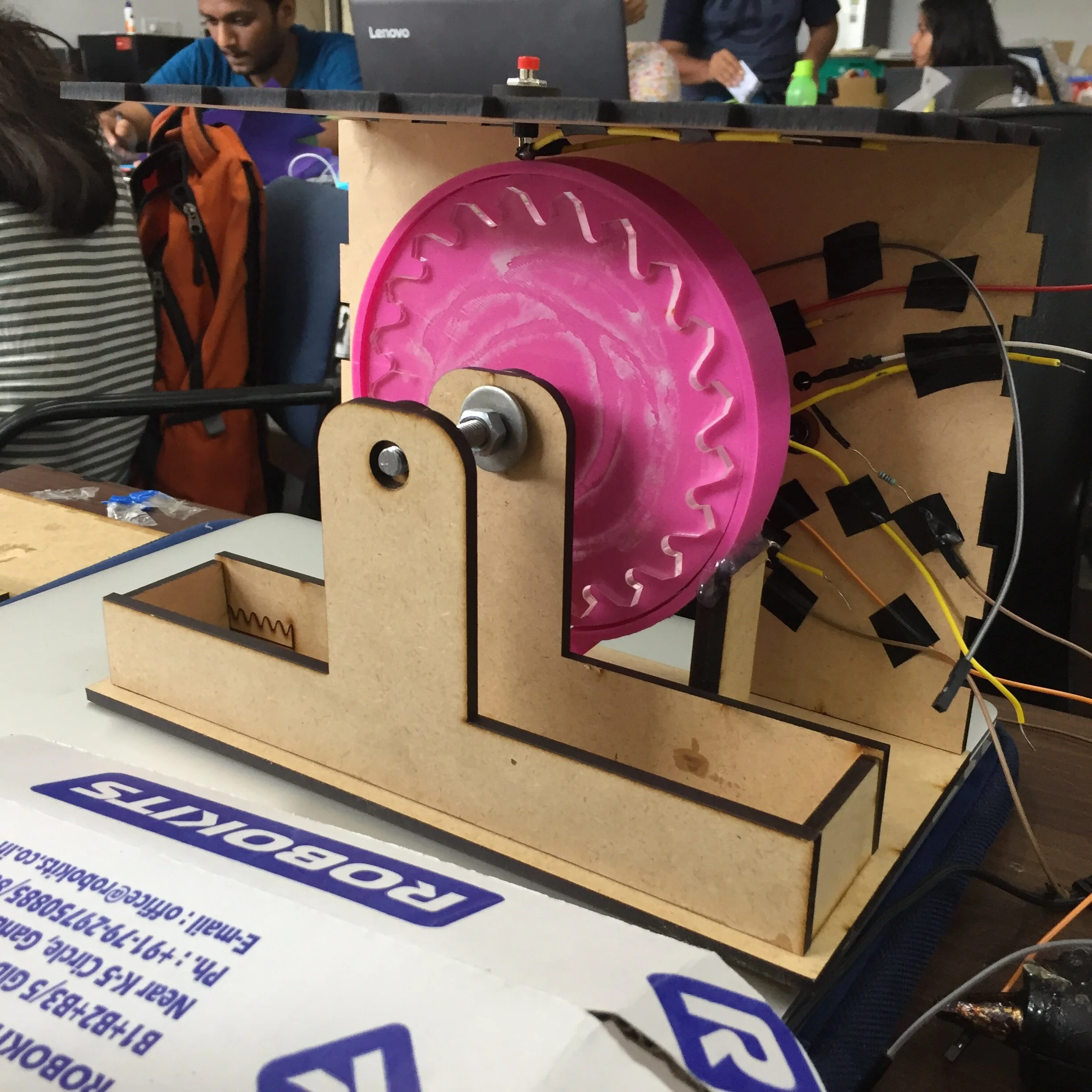

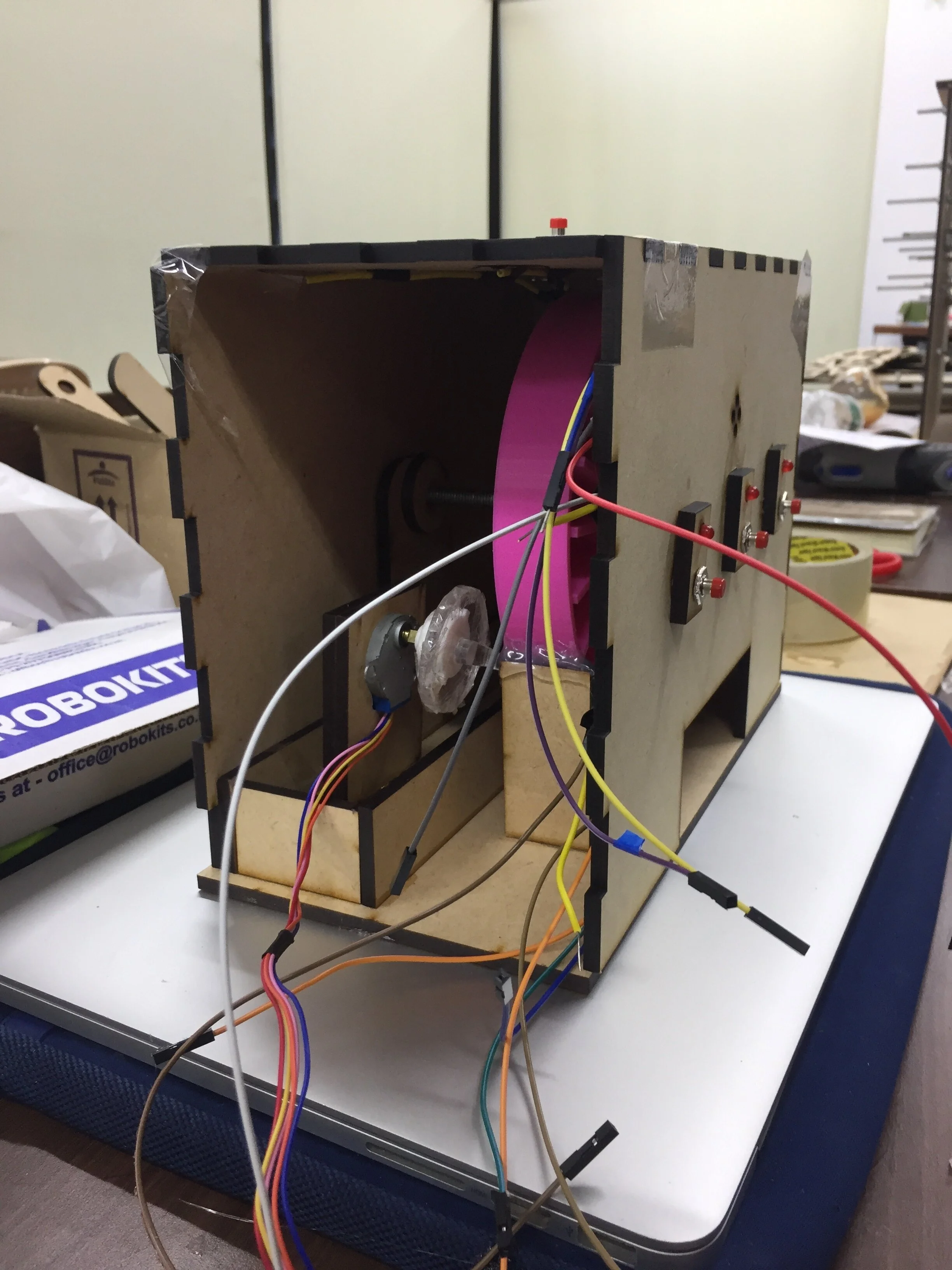

The next step was to figure out a dispensing mechanism for the device. We were looking for something convenient for the user and reliable in terms of manufacture. In our final design, the pills are stored in a carousel which has 21 compartments. The caregiver must open the back cover and fill each dose in each compartment, which can be labelled (Mon Morn, Mon Eve, etc) according to convenience. Once the patient completes the task (regardless of success or failure), a Geneva mechanism causes the correct pills to fall onto the tray.

A dc motor running a geneva mechanism

Long hours in the workshop

Once the concept was ready, we spent a good part of 3 weeks building the device. This involved the use of laser cutting, 3D printing, learning how to code an Arduino and a whole lot of trial and error! We were finally able to build a working prototype, complete with a housing for the motor, an alarm, LEDs and buttons.

Part 3: Medication Management

The last feature of the device is allowing a caregiver to manage the patient’s medication remotely. This involves setting up the reminders and alarms and getting notified in case of any mishap with the meds. The flowchart of the connection and the scenarios in which the caregiver may need to be contacted were rigorously worked out. The caregivers’ mobile app should allow them to reset alarms and change the difficulty level of the cognitive task on doctor's orders.

Patent Writing and Presentation

Parallely to building the device, we spent a lot of time researching prior art and writing the provisional patent application for our invention. Every week we would have our writing reviewed by our mentor, a patent lawyer from the US and have our device scrutinised by a panel of experts. The learning curve was very high and the the result was a complete patent draft and a lot of stage confidence!

Detailed Drawings for the Patent Application

Challenges and Learning

I consider these 6 weeks to be one of the most challenging times of my life. The process was something I had never seen before. Not only was I pushed completely out of my comfort zone, but I was also forced to learn a lot of new skills in limited time and taught to take complete ownership of my work. I went from not knowing what an Arduino was, to knowing how to code it, from not knowing anything about patent law to writing a complete patent application. Along the way, I met some truly inspiring people who pushed me to the limits of my potential!